One of the great things about games is their power to tell stories. Whether it's knights fighting dragons or German bureaucrats buying merchant houses, games can engross you in narratives that you create with your friends. My favourite game stories are those with troubling historical

settings: those periods when reprehensible actions led to positive

effects or good intentions created disasters. Unfortunately, most games

get in the way of these narratives by having contrivances that may make

for fun experiences but break the suspension of disbelief. Why are the

Catan's harbours built before anybody's settled the island? Why are the

richest real estate barons in New Jersey forced to stay at each other's

hotels? All too often, game designers focus on the puzzle-like and

competitive aspects of games, ignoring their storytelling potential.

It's possible to design a game that's interesting because of both the

challenge it poses and the stories it tells. It's hard, but when it

succeeds, it's amazing. Not attempting to create that connection between

the game, the players and a story is a missed opportunity.

One of the great things about games is their power to tell stories. Whether it's knights fighting dragons or German bureaucrats buying merchant houses, games can engross you in narratives that you create with your friends. My favourite game stories are those with troubling historical

settings: those periods when reprehensible actions led to positive

effects or good intentions created disasters. Unfortunately, most games

get in the way of these narratives by having contrivances that may make

for fun experiences but break the suspension of disbelief. Why are the

Catan's harbours built before anybody's settled the island? Why are the

richest real estate barons in New Jersey forced to stay at each other's

hotels? All too often, game designers focus on the puzzle-like and

competitive aspects of games, ignoring their storytelling potential.

It's possible to design a game that's interesting because of both the

challenge it poses and the stories it tells. It's hard, but when it

succeeds, it's amazing. Not attempting to create that connection between

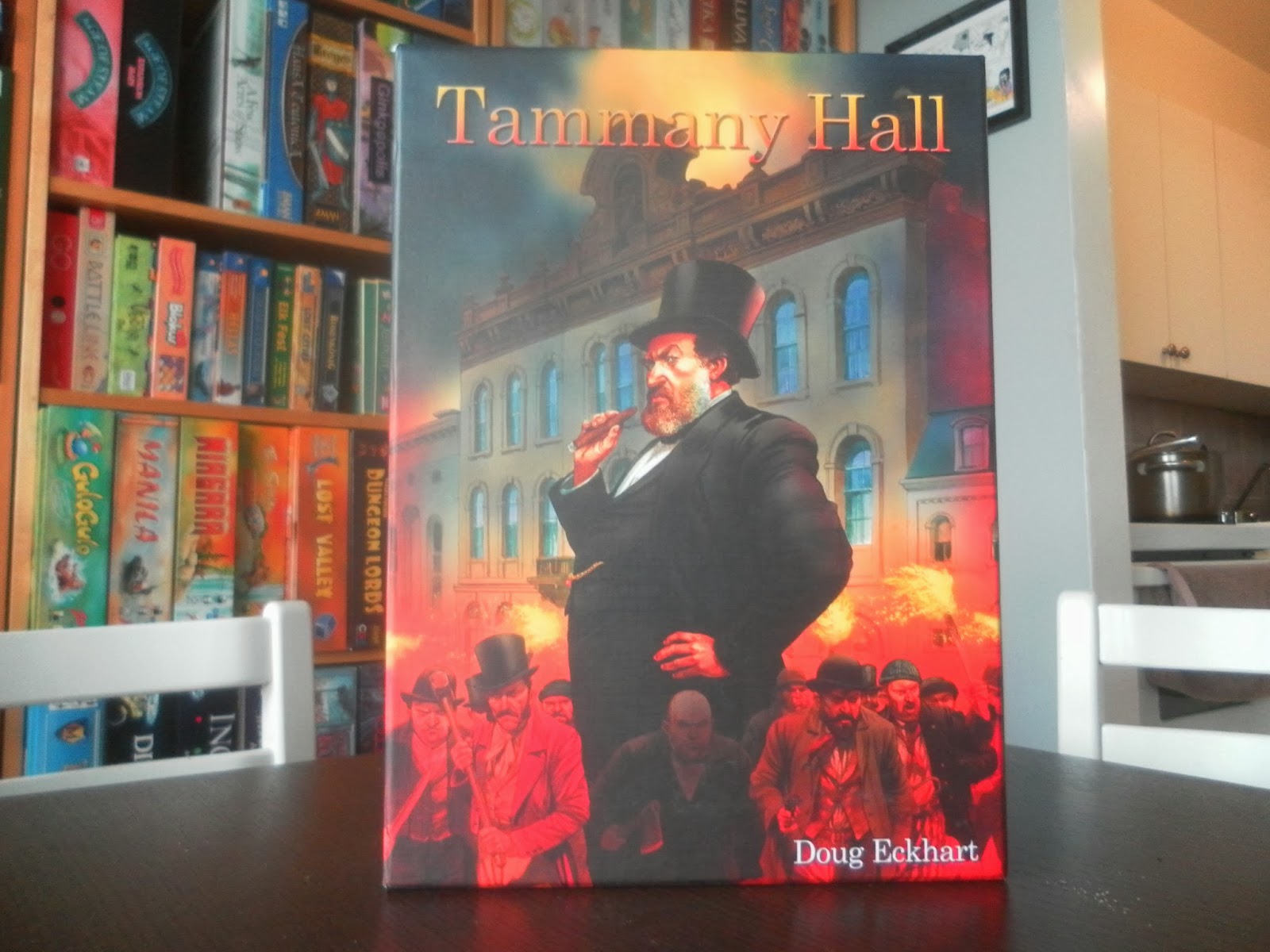

the game, the players and a story is a missed opportunity. No game capitalizes on that opportunity as well as Tammany Hall. Nothing feels shoehorned in; every aspect of the game flows naturally and logically from its setting and characters without sacrificing any strategic depth. The fact that the setting is 19th century New York City and the characters are corrupt politicians who stop at nothing to gain power makes me wonder whether Doug Eckhart designed the game specifically for me.

In Tammany Hall, your goal is to gain as much political power (points) as possible over sixteen years (rounds). Each turn, players send their ward bosses out into the city and help immigrants (Irish, English, Germans and Italians) settle in the various wards. Every time you place an immigrant cube into a ward, you gain a political favour chip of the corresponding colour. So, placing an Irish cube into a ward nets you an Irish favour token, because they owe you a favour for helping them out. This corresponds to how the Tammany Society gained control of New York City by providing social services to immigrants and gaining their loyalty.

The favour chips you accrue over the years can be used to help you win elections, which occur every four years. All the wards go to the polls. If you've got a boss in a ward, you participate in its election. Each boss you have there is a vote in your favour; players can add more votes by spending their favour chips in a blind bid, as long as the chips match the colour of an immigrant cube in the ward. So if you've been helping the Irish settle in the city, you can call in your favours and get their votes. But if there are only Germans in the ward, they don't really care how much the Irish love you. The player who has the most votes wins the ward and the loser gets kicked out. Then the next ward has an election and so on until all the wards have been decided.

Once the numbers come in, three things are evaluated. First, each player gets one point for every ward he won. Second, the “Immigrant Leader” positions are assigned: if you've got more immigrants of a certain community in your wards than any other player, you become that community's leader, gaining three of their favour chips as a prize. Finally, the player who won the most total wards becomes the Mayor, gaining three extra points. However, the Mayor must also hand out City Offices to each other player. These are special abilities that allow players to gain extra favours, move immigrants around or lock down valuable wards. So while the Mayor might have more points than any other player, she have to sit around for the next four years as the other players destroy her empire with the tools she has given them.

Those three results of an election combine together to create a fascinating tension. You want to win lots of wards so that you don't fall behind in points. But winning too many wards will make you Mayor and you'll be defenseless for the next four years. And if you're not paying attention to which wards you're winning, you'll likely miss out on the extra favours given to the Immigrant Leaders. So you have to direct your actions specifically, trying to win only the wards you need in order to get a good amount of points and become an Immigrant Leader while avoiding the mayoralty. Build up your own power and bleed your opponents dry. Lie in wait and the call in your favours in the final election to grab victory.

No matter what you do when playing the game, you'll be acting like a politician. Even sitting quietly at the table, ignoring the promises, the bluffs and the betrayals that are sure to be going on between the other players, you'll still be gerrymandering wards, moving immigrants to rearrange power structures and setting up ethnic enclaves. Tammany Hall turns placing cubes on cardboard into a lesson on the history of urban regime politics. All games should aspire to be so exciting, so engrossing and so enlightening.

On the eve of last year's Kickstarter campaign to reprint the game, Doug Eckhart wrote a blog post on the process of designing Tammany Hall. For me, the most shocking part of the story is that Eckhart was almost convinced to set the game in space. I'm shocked not because the game would be poorer for not having the beautiful board and erudite theme, but because such a change would have accomplished nothing. The game's design and its theme are inextricably tied together. It could have been called Space Station X-9, but any box of cardboard and wood that came with this rulebook would have unavoidably been about Tammany Hall.

Last Time: #6 - Time's Up!

Next Time: #4 - Bohnanza

All pictures taken by me.

No comments:

Post a Comment